Beyond Bitcoin: Trust-based Currencies

Beyond Bitcoin: Trust-based Currencies

I recently wrote an article about the brief history of money. That story ended with Bitcoin. In this article, I will write about trust-based currencies, which I believe are a much better alternative to cryptocurrencies.

For most people, the word “money” brings to mind banknotes and coins. Yet, we all know that a banknote is just a piece…thebojda.medium.com

When people think about money, they often imagine its physical form — banknotes and coins. However, in today’s world, we rarely use cash for payments. Instead, we mostly rely on bank cards, which are far more convenient. It’s easy to assume that the money on a bank card is the same as the cash we can hold in our hands. Many believe that the card is just a convenient tool and that the money it represents is safely stored in a bank vault. But this couldn’t be further from the truth!

When we check our bank account and see a balance of $1,000, it doesn’t mean that this amount exists in physical cash somewhere. It simply signifies that the bank owes us $1,000. The bank assures us that we can withdraw this money in cash from an ATM whenever we need to, though in practice, this is uncommon since using a bank card is much easier. It’s a bit like the “IOU notes” from Dumb and Dumber.

The money in our bank account is essentially the bank’s IOU to us, and this IOU functions as our medium of exchange. When we pay with a bank card, and the seller uses the same bank (eliminating the need for interbank transfers), the bank simply updates its internal records. For instance, if we spend $100 at a store, our account balance decreases to $900, while the store owner’s balance increases by $100. As long as we don’t withdraw cash from an ATM or trigger an interbank transfer, the bank only needs to shuffle these IOUs within its own system.

Here’s a simple example: Imagine we take out a $100 loan from the bank. The bank credits $100 to our account, which we can spend just like cash using our bank card. In doing so, the bank has effectively created money out of thin air. Now, we use this $100 at a store to purchase. To keep it simple, let’s assume the store owner also uses the same bank. In this case, the transaction is completed with a straightforward ledger adjustment. Later, when we repay the $100 loan, the bank cancels the debt, effectively removing the money it had created.

So, what’s really happening here? Since the money in our account represents the bank’s debt to us, taking out a $100 loan means we owe the bank $100, and the $100 credited to our account is the bank’s debt to us. When we spend this money at the store, we transfer the bank’s debt. After the transaction, the bank now owes the store owner $100, while we still owe $100 to the bank.

This leads to an important question: why do we even need the bank in this process? Why should I borrow money from the bank and pay interest, when I could simply buy on credit directly from the store and pay the store owner back later?

The answer is simple: the bank is seen as a highly reliable debtor, while we are not! But if that’s true, why does the bank trust us enough to lend us money when the store owner doesn’t? Why is it that the store owner won’t extend us credit, but the bank will?

When we take out a loan, the bank carefully evaluates the risk of lending us money. It assesses factors like our assets, regular income, and financial stability. If we fail to repay the loan, the bank has legal tools to recover the debt. For instance, they might auction off our car to cover what we owe.

The bank acts as an intermediary, transforming unreliable debt into reliable debt.

The modern monetary system is entirely built on trust. In essence, since banks create money out of nothing, money itself is nothing more than embodied trust! If you’re curious about the deeper history of money, check out my earlier article, which explores how money evolved from decentralized trust to centralized trust.

It’s natural that no one likes lending money to strangers, which is why we rely on a trustworthy intermediary: the bank. But what if there’s enough trust between the buyer and the seller? For instance, we’re often willing to lend hundreds of dollars to a friend or family member because we trust they’ll repay us. In such cases, where trust exists, a bank is unnecessary.

What about a friend’s friend? We don’t know them personally, but for a $100 transaction, we could lend the money to our friend, whom we trust, and they, in turn, could lend it to their friend, whom they trust. This concept can be called “transitive trust.”

Through this “transitive trust,” even longer lending chains can be established, removing the need for a bank. According to the “Six Degrees of Separation” theory, everyone on Earth is connected through an average of just six people. This suggests that relatively short lending chains could theoretically span the entire world, making banks as intermediaries unnecessary.

Manually managing these lending chains would be extremely complicated, but modern technology makes it easy to handle. The key requirement is a global accounting system that is secure, tamper-proof, and universally trusted. Fortunately, such a system already exists: the blockchain.

“Transitive trust” serves as the foundation for the Trustlines Network project, which brings this very concept to life on the Ethereum blockchain.

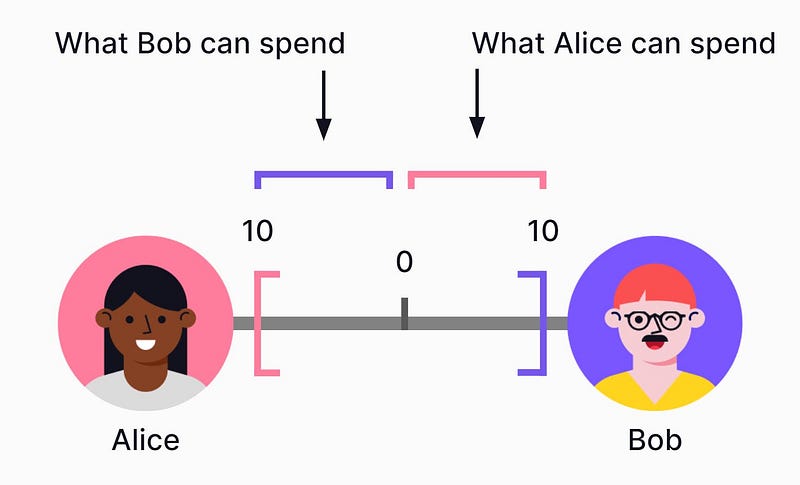

At the heart of the Trustlines Network is the credit line — a mutual line of credit established between two acquaintances. For example, Alice and Bob might agree on a $10 limit. If Alice buys apples from Bob for $5, the transaction is recorded, just like a bank ledger. Alice gets the apples, and the blockchain shows that she now owes Bob $5. Later, if Bob asks Alice to cut his hair and pays her $10, Alice’s debt is cleared, and Bob now owes Alice $5. Two financial transactions are completed seamlessly, without any need for a bank.

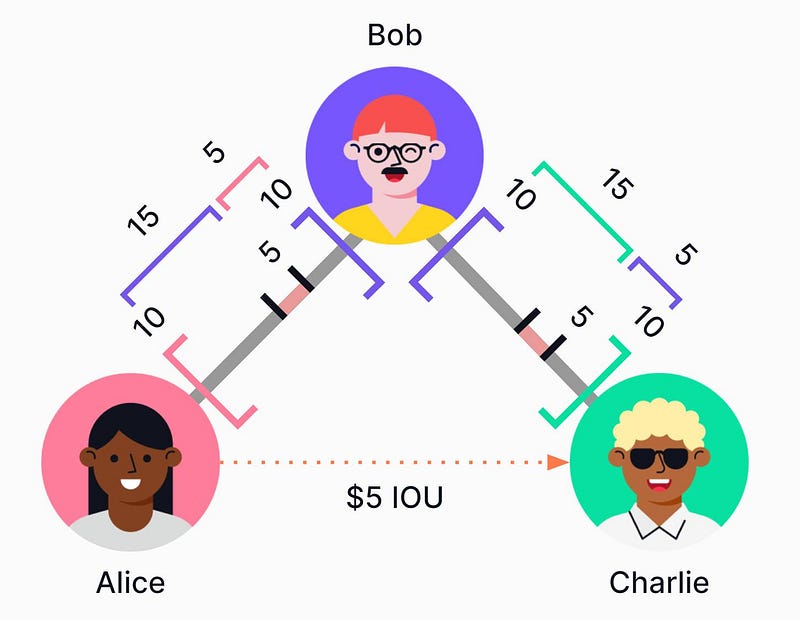

When a third person, who doesn’t know Alice, gets involved, “transitive trust” comes into play. Suppose Alice wants to buy a kilogram of pears from Charlie for $5, but she can’t pay him directly because they don’t know each other. However, Charlie knows Bob, so the transaction can be facilitated through Bob using a multi-hop payment. Charlie gives the pears to Alice, and the blockchain records that Alice owes Bob $5, while Bob owes $5 to Charlie. This demonstrates how the system enables transactions between strangers through a network of trusted relationships, eliminating the need for a bank as an intermediary. The only requirement is to identify a connection between the two parties.

Circles UBI operates on a similar principle, serving as a monetary system and a platform for implementing Universal Basic Income (UBI).

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is built on the idea that everyone should receive a regular monthly allowance by default. While the concept of “free money” might seem unusual at first, it has strong justifications. From a social and ethical perspective, it supports the fundamental right of every individual to live with dignity. Economically, UBI can also make sense. For instance, when people are not forced to work purely to survive, the labor market becomes more competitive, encouraging fairer wages. In this way, UBI can promote competition — a core principle of modern capitalist economies.

When discussing basic income, the first question is always, “Where will the funding come from?” According to classical economic theory, the government must collect taxes and redistribute the revenue as basic income. While this approach seems logical, alternative theories suggest it may not be the only solution.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), for example, proposes that the government can print money freely to fund socially important initiatives, such as unconditional basic income. Critics of MMT argue that printing money causes inflation, but MMT counters that inflation only occurs when the money supply outpaces available resources. Inflation happens when more money is allocated to each unit of resource, reducing the currency’s value. However, since resource availability fluctuates, MMT asserts that carefully managing the money supply can prevent hyperinflation.

To maintain economic stability, MMT acknowledges the importance of taxation. However, unlike classical theory — which views taxes as necessary to fund government expenditures — MMT sees taxes as a tool to regulate the money supply. According to MMT, taxes are not collected to finance spending (as that is achieved through money printing) but to remove excess money from circulation, helping to control inflation.

When basic income is funded through newly printed money, this approach is referred to as monetary basic income.

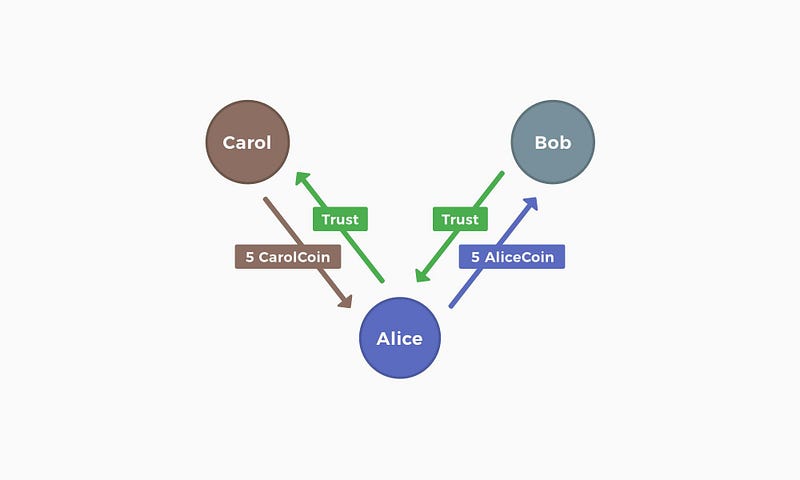

Circles UBI implements a form of monetary basic income directly on the blockchain. Instead of relying on a single, centrally issued currency, every participant creates their own unique currency. So, rather than a universal dollar, there’s an “Alice Dollar,” a “Bob Dollar,” and so on. It’s akin to each individual being their own country with a personal central bank, issuing their own currency.

This personal currency is distributed as basic income, facilitated by a smart contract. For example, Alice might receive 10 AliceCoins daily as her basic income, which she can use for her financial transactions. The controlled issuance of AliceCoins establishes its scarcity, a key requirement for it to function as a viable currency.

In Circles UBI, as in the Trustlines Network, trust determines whose currency is accepted by whom. For instance, if Bob trusts Alice, he will accept AliceCoin as payment. Similarly, if Alice trusts Carol, she will accept CarolCoin. These trust relationships are transitive, just like in the Trustlines Network.

If Carol wants to pay Bob, she would first need to exchange her CarolCoin for AliceCoin. Exchanges between trusted parties are always conducted on a 1:1 basis, ensuring simplicity and fairness in the system.

To prevent late joiners from being disadvantaged, the system incorporates continuous inflation, which gradually diminishes the early adopters’ advantage over time. Inflation also serves as a redistribution mechanism, helping to balance differences among participants. It functions like a wealth tax, where those with more wealth experience a greater impact. For example, if money loses 10% of its value annually, someone with $1,000 loses $100, while someone with $100 loses just $10. Since everyone receives the same basic income, this mechanism helps to reduce inequalities.

However, a challenge with this approach is that inflation can make it difficult for people to track prices. For instance, the price of a crate of apples will constantly fluctuate due to built-in inflation. To address this, the user interface could display inflation-adjusted values rather than the raw amounts. This way, if other factors like supply or demand remain stable, the price of apples would appear consistent on the interface, simplifying the user experience.

The currency mechanism in Circles UBI follows a similar logic to Bitcoin, where coins are distributed periodically, such as every 10 minutes. However, unlike Bitcoin, where miners compete to earn these coins, Circles UBI distributes them automatically and equally to its members. This approach ensures a more equitable system.

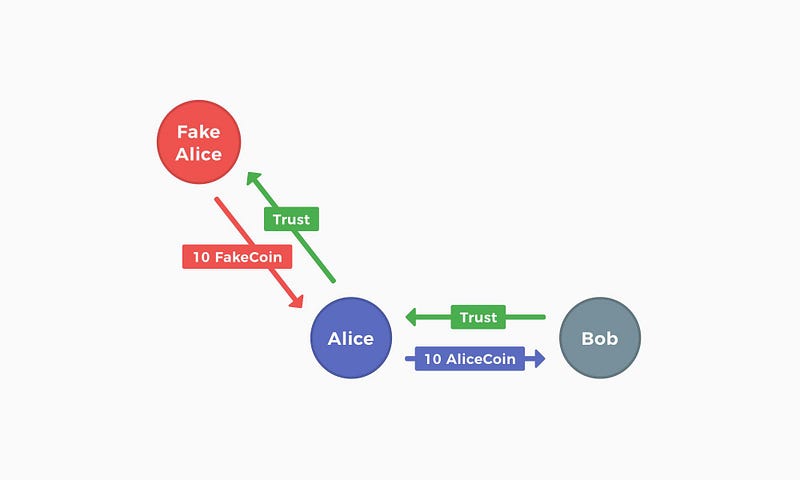

One of the key advantages of “transitive trust” systems is their resistance to Sybil attacks or the creation of fake accounts. For instance, if someone were to generate 1,000 fake accounts to collect basic income from each, it could potentially destabilize the system. However, in a transitive trust model, money can only circulate along trust-established paths. This means fake accounts are ineffective because no one will trust them.

For example, if Alice creates a fake account, it won’t provide any real benefit. Only Alice would accept the FakeCoin issued by the fake account, rendering it essentially useless.

However, these systems come with significant limitations. They only work effectively if the network is sufficiently dense. For instance, if Alice knows Bob and Carol knows Tom, Alice can trade with Bob, but she cannot trade with Carol or Tom since they lack a mutual connection. This connectivity issue is addressed by Karma, a network money concept I developed.

Have you ever thought about how money is created? Well, typically it is made out of nothing by banksbetterprogramming.pub

Karma replaces the “web of trust” with the concept of “proof of unique human.” This approach ensures that each person can have only one account, preventing the creation of fake accounts and enabling direct trading. Several third-party solutions can achieve this. For example, WorldID uses retinal scans to verify uniqueness, while Proof of Humanity employs a sophisticated web-of-trust approach. Additionally, any KYC (Know Your Customer) solution capable of guaranteeing user uniqueness can serve this purpose.

Karma’s core philosophy is that personal trust isn’t required. Instead, it relies on a large public ledger where everyone’s debts are transparently visible. A person’s reputation is tied to their level of debt, creating an incentive to manage and reduce it over time. Those who accumulate significant debts will face reduced willingness from others to engage in trade with them.

Karma simplifies this system using a basic ERC20 token, where every person starts with a balance of 0 that increases as they make payments (with the balance representing debt). Each individual is limited to a single Karma wallet, verified through WorldID or a Proof of Unique Human registration. Because it’s a standard ERC20 token, transactions can be conducted seamlessly through any compatible interface.

If Alice buys a crate of apples from Bob for $10, she incurs a $10 debt to Bob. Later, if Bob purchases pears from Carol for $10, he incurs a $10 debt to Carol. Finally, if Carol gets her hair cut by Alice for $10, she incurs a $10 debt to Alice. In this scenario, everyone has a $10 debt, visible on the public ledger. Resolving these circular debts is crucial to update members’ reputations.

This process, however, is not straightforward — it’s akin to finding a route on a map. To address this, the system employs “miners” who identify and resolve circular debt chains. When a miner discovers such a circle, they submit it to the system, which balances the debts, reducing everyone’s public debt to $0. Since members benefit from maintaining a good reputation, they pay a small transaction fee to the miners as an incentive for their work.

Although I used dollars as an example, Karma is primarily envisioned as a favor-based currency, where 100 karma represents one hour of work. This system could encourage a favor-driven economy. For instance, Bob mows Alice’s lawn, and out of gratitude, Alice pays him 100 karma. Later, Alice cuts John’s hair, and John pays her 100 karma. Finally, John gives Bob a ride when he’s hitchhiking, and Bob thanks him with 100 karma.

Rather than financial transactions, these are “favor transactions,” reflecting the philosophy of karma: when we do good for others, good things return to us. This system quantifies karma, turning it into a measurable currency.

In this way, Karma gamifies the act of doing favors, where members can strive to be the most generous and helpful individuals in their community.

I currently have a grant application under review with the World Foundation, where I requested support to implement this favor-based version of Karma as a mini-app on the WorldChain. Gamifying favors in this way might make the world a slightly better place. I wrote more about this project in detail in this article: Love on the Blockchain and the Gamification of Helping Others

Karma was initially designed to “favor money,” but as the example illustrates, it can also function as a complement to or even a replacement for the traditional monetary system. It operates like a peer-to-peer lending system where the collateral is the individual’s unique identity — a highly secure form of assurance.

If someone fails to repay their debt, they risk losing the trust of the entire network and being permanently excluded from the system, unable to receive credit from anyone again.

The trust-based currencies discussed above can serve as excellent complements to the existing monetary system and, in certain scenarios (such as local communities with localized economies), even replace it. The key realization is that the term “trust-based currency” is somewhat redundant — after all, all currencies rely on trust. The real distinction lies in whom we place our trust: the state, banks, smart contracts, assets, or one another.

It’s crucial to recognize that the blockchain-based currencies described here are not “play money.” They are just as legitimate as the money displayed in our bank accounts, backed by the same fundamental principle of trust.