Understanding Zero-Knowledge Proofs Through the Source Code of Tornado Cash

Understanding Zero-Knowledge Proofs Through the Source Code of Tornado Cash

Dive into the world of smart contracts with Zero-knowledge proof

Based on Wikipedia, the definition of the Zero Knowledge Proof (ZKP) is the following:

… zero-knowledge proof or zero-knowledge protocol is a method by which one party (the prover) can prove to another party (the verifier) that a given statement is true while the prover avoids conveying any additional information apart from the fact that the statement is indeed true. The essence of zero-knowledge proofs is that it is trivial to prove that one possesses knowledge of certain information by simply revealing it; the challenge is to prove such possession without revealing the information itself or any additional information.

The technology of ZKP can be widely used in many different fields like anonymous voting or anonymous money transfer that are difficult to solve on a public database like the blockchain.

Tornado Cash is a coin mixer that you can use to anonymize your Ethereum transactions. Because of the logic of the blockchain, every transaction is public. If you have some ETH on your account, you cannot transfer it anonymously, because anybody can follow your transaction history on the blockchain. Coin mixers, like Tornado Cash, can solve this privacy problem by breaking the on-chain link between the source and the destination address by using ZKP.

If you want to anonymize one of your transactions, you have to deposit a small amount of ETH (or ERC20 token) on the Tornado Cash contract (ex.: 1 ETH). After a little while, you can withdraw this 1 ETH with a different account. The trick is that nobody can create a link between the depositor account and the withdrawal account. If hundreds of accounts deposit 1 ETH on one side and the other hundreds of accounts withdraw 1 ETH on the other side, then nobody will be able to follow the path where the money moves. The technical challenge is that smart contract transactions are also public like any other transaction on the Ethereum network. This is the point where ZKP will be relevant.

When you deposit your 1 ETH on the contract, you have to provide a “commitment”. This commitment is stored by the smart contract. When you withdraw 1 ETH on the other side, you have to provide a “nullifier” and a zero-knowledge proof. The nullifier is a unique ID that is in connection with the commitment and the ZKP proves the connection, but nobody knows which nullifier is assigned to which commitment (except the owner of the depositor/withdrawal account).

Again: We can prove that one of the commitments is assigned to our nullifier, without revealing our commitment.

The nullifiers are tracked by the smart contract, so we can withdraw only one deposited ETH with one nullifier.

Sounds easy? It’s not! :) Let’s go deep inside the technology. But before anything, we have to understand another tricky thing, the Merkle tree.

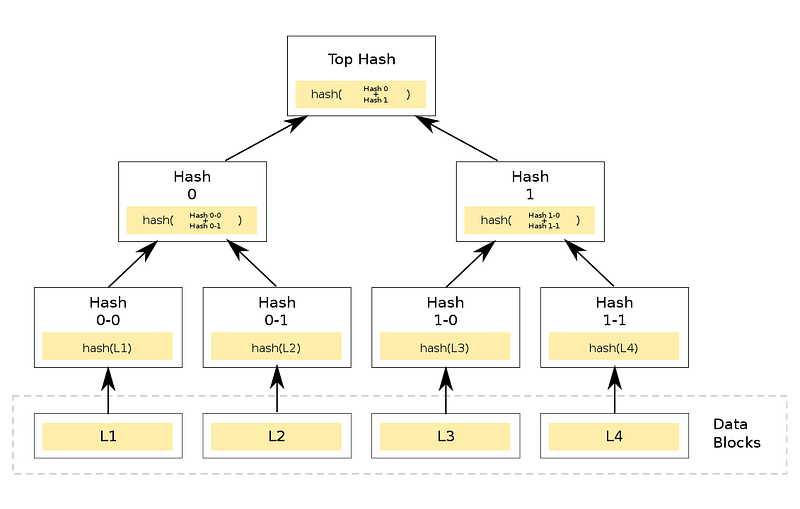

Merkle trees are hash trees, where the leaves are the elements, and every node is a hash of the child nodes. The root of the tree is the Merkle root, which represents the whole set of elements. If you add, remove, or change any element (leaf) in the tree, the Merkle root will change. The Merkle root is a unique identifier of the set of elements. But how can we use it?

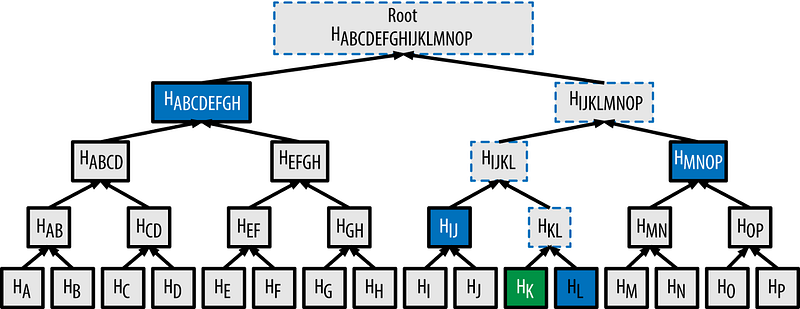

There is another thing called Merkle proof. If I have a Merkle root, you can send me a Merkle proof that proves that an element is in the set that is represented by the root. The figure below shows how is it working. If you want to prove to me that HK is in the set, you have to send me the HL, HIJ, HMNOP, and HABCDEFGH hashes. Using these hashes I can calculate the Merkle root. If the root is the same as my root then HK is in the set. Where can we use it?

A simple example is whitelisting. Imagine a smart contract that has a method that can be called by only whitelisted users. The problem is that there are 1000 whitelisted accounts. How can you store them on the smart contract? The simple way is to store every account in mapping, but it is very expensive. A cheaper solution is building a Merkle tree, and storing the Merkle root only (1 hash vs 1000 is not bad). If somebody wants to call the method she has to give a Merkle proof (in this case it is a list of 10 hashes) that can be easily validated by the smart contract.

Again: A Merkle tree is used to represent a set of elements with one hash (the Merkle root). The existence of an element can be proven by the Merkle proof.

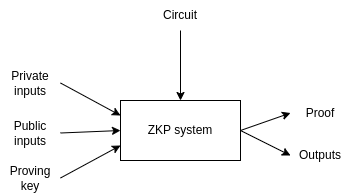

The next thing that we have to understand is the zero-knowledge proof itself. With ZKP, you can prove that you know something without revealing the thing that you know. For generating a ZKP, you need a circuit. A circuit is something like a small program that has public inputs and outputs, and private inputs. These private inputs are the knowledge that you don’t reveal for the verification, this is why it is called zero-knowledge proof. With ZKP, we can prove that the output can be generated from the inputs with the given circuit.

A simple circuit looks like this:

pragma circom 2.0.0;

include "node_modules/circomlib/circuits/bitify.circom";

include "node_modules/circomlib/circuits/pedersen.circom";

template Main() {

signal input nullifier;

signal output nullifierHash;

component nullifierHasher = Pedersen(248);

component nullifierBits = Num2Bits(248);

nullifierBits.in <== nullifier;

for (var i = 0; i < 248; i++) {

nullifierHasher.in[i] <== nullifierBits.out[i];

}

nullifierHash <== nullifierHasher.out[0];

}

component main = Main();Using this circuit, we can prove that we know the source of the given hash. This circuit has one input (the nullifier) and one output (the nullifier hash). The default accessibility of the inputs is private, and the outputs are always public. This circuit uses 2 libraries from the Circomlib. Circomlib is a set of useful circuits. The first library is bitlify that contains bit manipulation methods, and the second is pedersen which contains the Pedersen hasher. Pedersen hashing is a hashing method that can be run efficiently in ZKP circuits. In the body of the Main template, we fill the hasher and calculate the hash. (For more info about the circom language, please take a look at the circom documentation)

For generating the zero-knowledge proof, you will need a proving key. This is the most sensitive part of ZKP because using the source data that is used to generate the proving key, anybody could generate fake proofs. This source data is called the “toxic waste” that has to be dropped. Because of this, there is a “ceremony” for generating the proving key. The ceremony has many members and every member contribute to the proving key. Only one non-malicious member is enough to generate a valid proving key. Using the private inputs, the public inputs, and the proving key, the ZKP system can run the circuit and generate the Proof and the outputs.

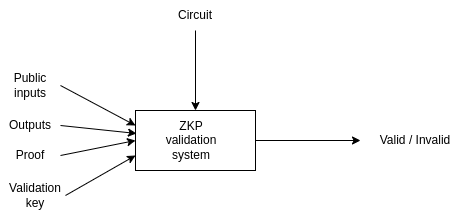

There is a validation key for the proving key that can be used for the validation. The validation system uses the public inputs, the outputs, and the validation key to validate the proof.

Snarkjs is a full-featured tool to generate the proving key and the verification key by the ceremony, generate the proof, and validate it. It can also generate a smart contract for the verification, that can be used by any other contract to validate the zero-knowledge proof. For more information, please look at the snarkjs documentation.

Now, we have everything to understand how Tornado Cash (TC) works. When you deposit 1 ETH on the TC contract, you have to provide a commitment hash. This commitment hash will be stored in a Merkle tree. When you withdraw this 1 ETH with a different account, you have to provide 2 zero-knowledge proofs. The first proves that the Merkel tree contains your commitment. This proof is a zero-knowledge proof of a Merkle proof. But this is not enough, because you should be allowed to withdraw this 1 ETH only once. Because of this, you have to provide a nullifier that is unique for the commitment. The contract stores this nullifier, this ensures that you don’t be able to withdraw the deposited money more than one time.

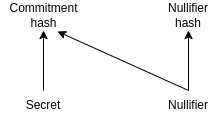

The uniqueness of the nullifier is ensured by the commitment generation method. The commitment is generated from the nullifier and a secret by hashing. If you change the nullifier then the commitment will change, so one nullifier can be used for only one commitment. Because of the one-way nature of hashing, it’s not possible to link the commitment and the nullifier, but we can generate a ZKP for it.

After the theory, let’s see how the withdraw circuit of TC looks like:

include "../node_modules/circomlib/circuits/bitify.circom";

include "../node_modules/circomlib/circuits/pedersen.circom";

include "merkleTree.circom";// computes Pedersen(nullifier + secret)

template CommitmentHasher() {

signal input nullifier;

signal input secret;

signal output commitment;

signal output nullifierHash; component commitmentHasher = Pedersen(496);

component nullifierHasher = Pedersen(248);

component nullifierBits = Num2Bits(248);

component secretBits = Num2Bits(248);

nullifierBits.in <== nullifier;

secretBits.in <== secret;

for (var i = 0; i < 248; i++) {

nullifierHasher.in[i] <== nullifierBits.out[i];

commitmentHasher.in[i] <== nullifierBits.out[i];

commitmentHasher.in[i + 248] <== secretBits.out[i];

} commitment <== commitmentHasher.out[0];

nullifierHash <== nullifierHasher.out[0];

}// Verifies that commitment that corresponds to given secret and nullifier is included in the merkle tree of deposits

template Withdraw(levels) {

signal input root;

signal input nullifierHash;

signal private input nullifier;

signal private input secret;

signal private input pathElements[levels];

signal private input pathIndices[levels]; component hasher = CommitmentHasher();

hasher.nullifier <== nullifier;

hasher.secret <== secret;

hasher.nullifierHash === nullifierHash; component tree = MerkleTreeChecker(levels);

tree.leaf <== hasher.commitment;

tree.root <== root;

for (var i = 0; i < levels; i++) {

tree.pathElements[i] <== pathElements[i];

tree.pathIndices[i] <== pathIndices[i];

}

}component main = Withdraw(20);The first template is the CommitmentHasher. It has two inputs, the nullifier and the secret which are two random 248-bit numbers. The template calculates the nullifier hash and the commitment hash which is a hash of the nullifier and the secret as I wrote before.

The second template is the Withdraw itself. It has 2 public inputs, the Merkle root, and the nullifierHash. The Merkle root is needed to verify the Merkle proof, and the nullifierHash is needed by the smart contract to store it. The private input parameters are the nullifier, the secret, and the pathElements and pathIndices of the Merkle proof. The circuit checks the nullifier by generating the commitment from it and from the secret and also checks the given Merkle proof. If everything is fine, the zero-knowledge proof will be generated that can be validated by the TC smart contract.

You can find the smart contracts in the contracts folder in the repo. The Verifier is generated from the circuit. It is used by the Tornado contract to verify the ZKP for the given nullifier hash and Merkle root.

The easiest way to use the contract is the command-line interface. It is written in JavaScript, and its source code is relatively simple. You can easily find where the parameters and the ZKP are generated and used to call the smart contract.

Zero-knowledge proof is relatively new in the crypto world. The math behind it is really complex and hard to understand, but tools like snarkjs and circom make it easy to use. I hope, this article helps you to understand this “magical” technology, and you can use ZKP in your next project.

Happy coding…

UPDATE: I have a new article about the topic:

And another article about how I built a JavaScript library for anonymous voting based on the source code of Tornado Cash. This is a step-by-step tutorial with circom, Solidity, and JavaScript codes: